Author: Menterra

Impact investment fund Menterra invests in two companies

Menterra, an impact investment fund that will invest in early-stage social enterprises, has announced its investment in two ventures – Biosense Technologies, which develops and delivers point-of-care diagnostics solutions; and, Nubesol, an agri-business company that provides precision farming services to sugar companies. It did not disclose the amount that it invested.

Menterra Floats $6M Social VC Fund

Menterra Venture Advisors said on Tuesday it has launched its maiden fund in India with a corpus of Rs 40 crore (about $6 million).

Hardware Innovation is … Hard

Hardware Innovation is… Hard: How Four Entrepreneurs Overcame the Challenges

So, Walmart recently agreed to buy a majority stake in Flipkart – a popular mobile app-based online retailer in India – for $16 billion. That’s roughly a billion for the founder, who started his app-based innovation with about $1,500. “Good for him!” I thought. Not too many have such luck. And then I immediately thought about an expectant mother in rural Maharashtra, India, whose version of luck was being able to deliver her baby and survive the process, since her anemia was diagnosed fairly early and she has been on iron supplements to counter it.

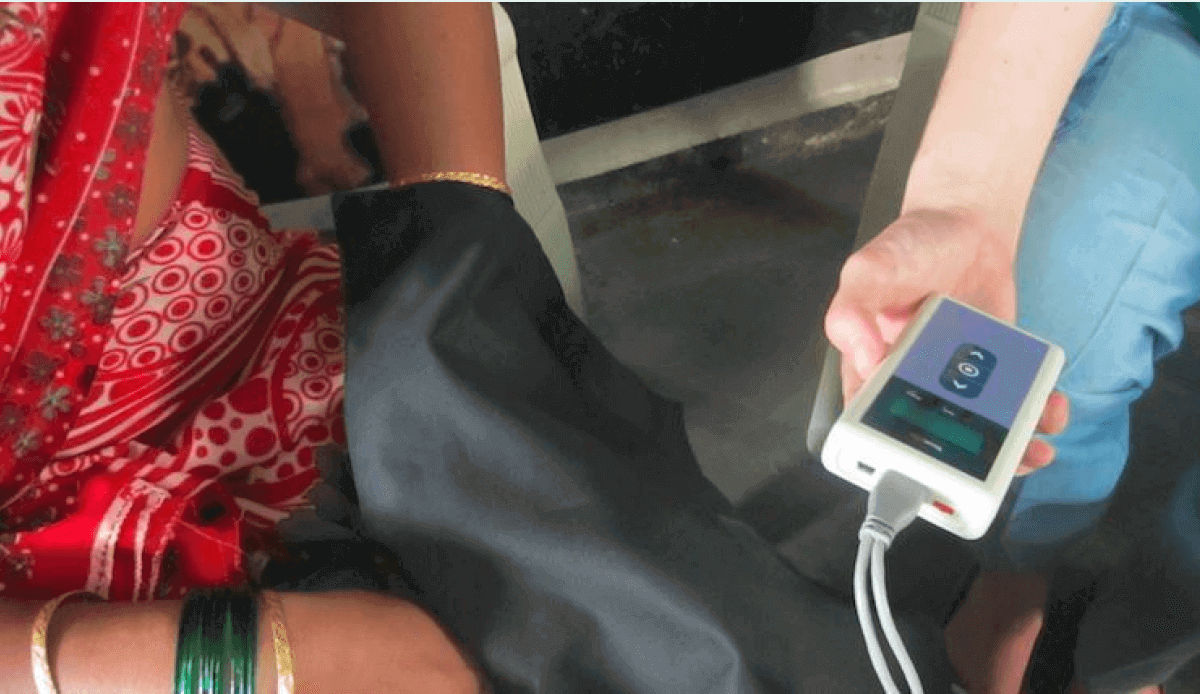

It is not all luck, actually: Her survival (and that of thousands of other mothers) is possible, in large part, thanks to a non-invasive anemia screening device from Biosense. She might not understand the concept of an app, let alone shopping on Flipkart, but the impact of the hardware-led innovation that led to her survival is all too real to her.

(Note: Biosense and the other companies mentioned have received investment capital from Villgro, where the author serves as chief technology officer and health care practice lead).

HARDWARE-LED INNOVATION IS…HARD!

It was one such rural mother, whose luck had run out in a peripheral health center where undiagnosed anemia took her life, that motivated Biosense co-founders Dr. Abhishek Sen and Dr. Yogesh Patil to embark upon a journey of innovation and entrepreneurship. It was a radically new path for these freshly minted physicians. Fast forward seven years and Biosense is in scaling mode, having grown slowly, painfully and steadily into an entity focussed both on its original mission of serving public health needs – and also on reaching a sizable share of the private health care market in India. But its journey was not as “utopian” as Flipkart’s. For starters, hardware-led innovations are, for lack of a better word, really hard to pull through. The resources and time required to churn out iterations are much larger, even if one has a clear understanding of the problem-solution fit and the design expertise needed. Additionally, the lack of a mature ecosystem to support such hardware-centric enterprises is a stumbling block. The journey of a social entrepreneur is fraught with a minefield of crippling mistakes and cash-robbing redesigns. It is not surprising that many entrepreneurs and investors avoid risking their resources on such ventures.

KNOW WHO WILL PAY FOR IT, WHY AND HOW MUCH

Another complication is the fact that the buyer of this type of innovation is distinctly different from the user, who in turn is entirely different from the beneficiary. Even a simple innovation is bound to become a lot more complex to deploy if all these different stakeholders have to be satisfied. The Bempu bracelet by Ratul Narain is one such example. Designed as a simple intervention to reduce infant mortality due to hypothermia, the bracelet measures the infant’s temperature and raises an alarm when it falls. Worn by the infant and monitored by the caregiver, it is an effective solution – but who will buy it and help deploy it?

That is a seemingly simple question with multiple complex answers. In the Indian context, it is the government that is capable of purchasing this at scale, and is also tasked with reducing infant mortality – especially the state government, which is responsible for public health. But to complicate matters, the state health budget has two components, funded and approved at two different levels: Suddenly, identifying the buyer is not so obvious. In some ways, the biggest thing Narain had to accomplish was NOT designing the bracelet, but figuring out which line item in the budget is the key to a government sale. But he realises that while this path is clearer now, it is certainly not a sprint to the end, but a marathon – 29 states in India means at least that many stakeholders to convince – pilot after pilot after pilot.

RADICAL INNOVATION REQUIRES HEAVY CONCEPT SELLING

Imagine the plight of K.S. Satish, the founder of Flybird Innovations, who discovered this reality the hard way and had to overcome it without running out of cash. Satish was a 13-year veteran of aerospace R&D and product development, but passionate about agriculture. There was an acute water shortage in his hometown of Chitradurga, and yet farmers were not using irrigation technology – mostly because small farmers couldn’t afford it. So he left his job and started creating a product for water management – a controller that automated water delivery to crops. After some hard knocks, he pivoted to an efficient drip irrigation system, enough to satisfy a small farmer’s needs, at an attractive price.

But selling a radically new farming practice required significant behavior change, and hence extensive concept selling. He started doing small demos at farmer fairs and saw some traction, but achieving serious scale required big sales muscle – Flybird was too small to attract such talent. Though Satish’s story has a pleasant ending – he managed to get a co-distribution/co-branding solution with a major agribusiness – many hardware-led enterprises flounder and slowly fail because they underestimate the stamina required to tackle this dissemination step. Unless well-planned and executed, the cost of sales/customer acquisition for these one-product companies quickly becomes prohibitive to enable scale.

All these innovators did get one aspect right – they were able to leverage the support their ecosystem partners offered vis-a-vis mentoring, knowledge, networks, etc., and navigate the challenges a typical hardware-led innovative enterprise faces. But such partners are also few and far between, a gap that Villgro hopes to fill in its mission to create impactful, innovative and successful enterprises. With our investment and outreach programs iPitch and Unconvention, and through partners like ASME iShow, BIRAC and the DFID-funded INVENT program, Villgro strives to support many such innovators – who went well beyond tapping and swiping!

I respect and empathise with the plight of these innovators, and wonder if the ecosystem will mature fast enough to offer them enough support before the hard path of app-less-ness consumes them. Yet I am touched by the fact that this enthusiastic lot is laboring on, fueled by the smiles on the faces of their beneficiaries – although they assure me that they would also gladly take the next billion-dollar exit!

Arun Venkatesan is the chief technology officer and health care practice lead at Villgro.

Bengaluru-based Curiositi Learning Solution raises funding from Menterra

Menterra has announced its latest investment in the education sector – Bengaluru-based Curiositi Learning Solutions, which develops learning programs that uniquely integrate the benefits of activity-based learning with personalized software

Social action in India: Past, present, future

Looking at social action in India from 1947 onwards, and given where we are today, here’s why we need civil society as a balancing force between the state and markets.

Based on Vijay Mahajan’s essay ‘A Retrospective Overview of Social Action in India: 1817-2017’, this three minute video gives you a brief history of social action in India. Watch it here, or scroll down for the slideshow.

Social action is an aggregation of efforts by various individuals to address what they see as the social problems of their times. Thus, before we think about the future of social action in India for the next 30 years, we need to think more fundamentally about our role as individuals in society.

Unfortunately, the overwhelming concerns for survival and securing livelihoods, and the growing influence of market institutions have converted most relationships between individuals into mere transactions. We have reduced ourselves to producers and consumers, sellers and buyers. The interactional aspect of relationships has taken a back seat.

“TODAY, A CITIZEN IS NOTHING MORE THAN THE RELATIONSHIP THEY HOLD WITH THE STATE.”

On the other hand, the rise of the state—including its encroachment on essentially social sectors such as health and education in the name of welfare—has reduced the definition of the word ‘citizen’. Today, a citizen is nothing more than the relationship they hold with the state. In a recent speech, Rajesh Tandon, founder of Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA), argued that we need to broaden the concept of citizenship from being a vertical relationship between the individual and the state, to numerous horizontal relationships among individuals.

The third level at which people relate is one that encompasses the natural world or environment, as well as the spiritual—the need to find meaning and purpose in our daily lives.

Therefore, an individual who is not only engaged in transactions and interactions, but has humane relationships with others, cares for nature, and cultivates their spiritual side is more evolved than the mere producer-consumer archetype.

The central challenge of the 21st century then, is to build robust eco-social action-oriented institutions that can nurture such individuals across income, caste, and class levels.

These eco-social instituions (ESIs) are therefore civil society organisations of the future; they focus on changing environmental and social norms—critical for the future of the planet.

The role of eco-social institutions

There are at least six reasons to build robust eco-social institutions.

- ESIs promote diversity and pluralism. They are like bio-diversity reserves for preserving a vast variety of ideas and beliefs, necessary for the survival and evolution of humanity.

- They serve as incubators for innovative approaches to resolve problems, which neither the state nor the market have been able to crack.

- They can act as ‘practice fields’ for democracy, where people form numerous neighbourhood groups and wider social associations to address a number of needs and issues. These collectives provide them the practice for political democracy.

- ESIs can act as early warning mechanisms that are able to detect and amplify anxieties on the ground, among the people, and alert society, the state and the market to take corrective action.

- They play a balancing role between the state and market institutions and are essential for ‘restoring sanity’ whenever either of these crosses a line. ESIs can influence political change and enable pro-consumer and pro-environment laws to control market players.

- Finally, they are focused on enhancing the overall well-being of all people. Market institutions are designed for maximising profits, while state institutions are designed for maximising power, control, or order.

Eco-social institutions therefore have a huge responsibility to work at the normative level, that is, establishing principles of what is widely accepted as desirable for the long term good of individuals in a society. This is partly because governments have ripped the normative fabric of society in the name of social good.

“WE NEED A NORMATIVE VISION THAT WILL ENSURE LIBERTY OF LIFE AND BASIC FREEDOMS.”

We need a normative vision that will ensure liberty of life and basic freedoms—of expression, belief, occupation and association, a safe and clean habitat, with a minimum level of health, education, economic opportunity, political representation, and cultural self-expression for all.

The state as well as market institutions have failed to offer these to us. It is time that ESIs step in and influence both the state and the market. If the 21st century has to avoid the folly of the reassertion of the state in response to the excesses of the market, ESIs need to be strengthened, as a balancing force between the state and market institutions.

Using eco-social institutions to influence the state

In order to provide primacy to ESIs, several constitutional and legal amendments are required. These would:

- Make the Directive Principles a conjoint responsibility of the state and eco-social institutions by amending Article 38 (1) to read as follows: “The State shall strive, directly as well as by enabling associations of citizens, to promote the welfare of the people…”.

- Establish a permanent national commission on eco-social institutions so that there could be an interface between the state and civil society.

- Advocate that the Finance Commission as well as the State Finance Commissions devolve at least a minimum portion of their tax revenues to ESIs.

- Broaden the ambit of the Comptroller and Auditor General, the Central Vigilance Commission, and the Central/State Information Commissions to cover social institutions. Doing this would bring social institutions at the same level of accountability and transparency as they expect from state institutions.

- Ensure that the Union and the State Public Service Commissions—which are responsible for recruitment of candidates to the various civil services—have at least two members from the social sector to ensure the selection of right people in public service.

Using eco-social institutions to influence the market

Business has acquired enormous power to mould and control our lives; it is necessary that businesses and market institutions are influenced by eco-social thinking. To ensure this,

- Companies and regulatory commissions must have at least two board members from the social sector.

- Universities and professional schools must have adequate representation from the social sector on their boards; they must also offer courses on social sector issues.

- At least 50 percent of CSR funds should be given to independent social institutions to undertake various programmes.

- Users and consumers must be organised as a countervailing force against the untrammelled power of large companies.

Building effective institutions for eco-social action

The time has come for individuals to evolve from being passive participants in market institutions—producers and consumers, or passive recipients of state entitlements and welfare services.

To go beyond the control of market and state institutions, individuals imbued with a deep ecological and spiritual consciousness need to come together and form a new generation of eco-social institutions. Inspiration, leadership, legitimacy and resources are crucial for making ESIs more effective. Each of these can be and will have to be developed systematically to make such institutions more responsive, participatory, efficient, accountable and transparent.