Menterra Venture Advisors, a Bangalore based venture capital firm, along with its investment partner Artha Venture Challenge, an initiative by Artha Platform to find social entrepreneurs, announced a new round of investment in Biosense Technologies

Author: Menterra

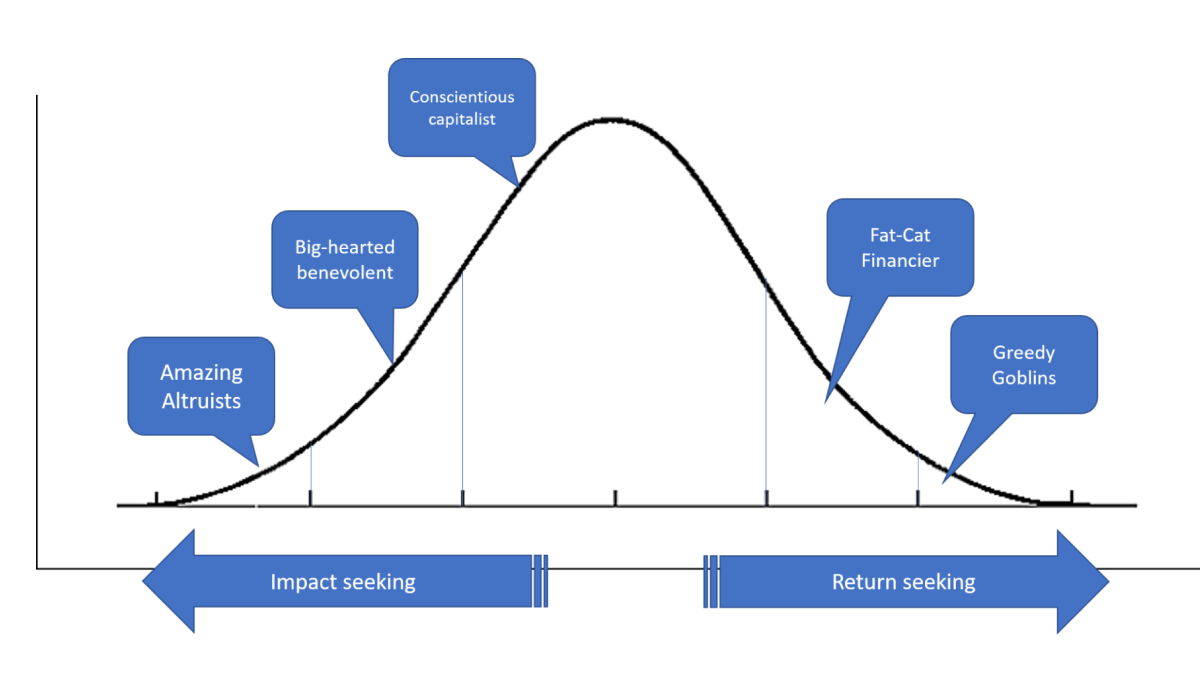

The bell curve of altruism

We need to look beyond our existing definitions and approaches to Funding, Talent, and Partnerships, if we are to address Social problems at Scale.

One often hears the question (and you’ve probably asked this yourself): “What is the role of private enterprise in addressing social problems?” The general belief is that the moment you allow return-seeking capital, you are opening the door for exploitation. After all, how can you profit from the poor?

These may be fair concerns, but for-profit, impact-seeking private enterprise has a role to play in development; and this article is an attempt to articulate why.

The Limitations of traditional approaches

The development problems we face are large and complex. Income inequity, poor health outcomes, low rates of educational achievement, low farm productivity—everywhere you turn, you see these issues staring you in the face. Some of these are hundreds of years old, deeply intertwined with other issues, and seemingly intractable.

While government has the potential to scale, it is not designed to experiment with risky solutions.

Traditional ways of addressing these have been through government intervention (such as targeted schemes), or through initiatives of nonprofits. While the government has deep pockets and the potential to scale, it is not designed to innovate, or experiment with risky but potentially game-changing solutions.

While government has the potential to scale, it is not designed to experiment with risky solutions.Nonprofits, on the other hand, struggle with finding the talent and resources required to scale. The donor shift to project-based financing also means that they don’t have the ability to experiment too much with new and innovative, but risky, approaches.

Lastly, solving these complex problems requires collaboration. Parties working on different parts of the problem must work together, contributing what they individually do best, while also collectively making a difference on the whole. However, without the resources–people and money–to engage partners effectively, attempts at collaboration often break down.

Related article: Building coalitions

THE RETURN VS IMPACT MOTIVATION

To address these problems at scale, what can we do to increase the flow of money, talent and partnership, support to develop, deploy and scale innovative solutions for our most pressing problems?

I like to think of these in terms of the ‘Bell Curve of Altruism.’ If there was an index of altruism, I believe that funders—both individual as well as institutional–would generally be distributed normally along that index.

On the extreme left would be the Amazing Altruists, people who readily give their money and time to causes they believe in. On the other extreme are what I’d like to call Greedy Goblins who don’t think much about the impact of their actions, as long as they continue to make more money doing it.

I think most would fall in the middle, where they’d like to see fair returns, but are conscious about how those returns are earned—fairly and legally.

If we have to increase the flow of capital to social causes, we have to be able to move beyond the Amazing Altruists and draw in the Big-hearted Benevolents, and some of the Conscientious Capitalists.

While Altruists are willing to give their money as pure grants, expecting nothing but social impact in return, Benevolents need a little more—they expect to get at least their capital back, and are willing to be patient about it. The Conscientious Capitalist may be willing to accept a lower-than-market return, but expects the investee to at least cover inflation, and maybe a little more.

At Villgro, a nonprofit, we’re firmly in Altruist territory. However, to expand the pool of capital available to the social entrepreneurs we work with, we launched the Menterra Social Impact Fund, which gives muted returns, with social impact. We were thus able to tap into the Benevolents and Conscientious Capitalists and expand our footprint of financial supporters.

The same logic can be applied to people as well. We need hundreds of social change agents at all levels, within both nonprofits and social businesses, if we have to make a dent in the size of problems we face.

We need social change agents at all levels, within both nonprofits and social businesses, if we have to make a dent in the size of problems we face.

Some of the best entrepreneurs we’ve seen, are those who have gained valuable experience working at a corporate. When they evaluate the decision to take the plunge into solving a social problem, the ‘opportunity loss’ in giving up the security and quantum of the corporate paycheck weighs heavily on their decision.

We need social change agents at all levels, within both nonprofits and social businesses, if we have to make a dent in the size of problems we face.

People sitting just outside the Amazing Altruist territory–2-3 percent of the population–want their basic material needs to be met. They have families to support and student loans to pay.

Founders of social enterprises might be willing to make the sacrifice, knowing that their shareholding will compensate them in the future, when their social enterprise gets acquired. But companies aren’t built on founders alone; one needs senior and middle management to execute and scale.

Related article: How to crack the talent test

If we have to increase the flow of smart, capable, talented people addressing social problems to the sector, we have to meet the needs of the people in the upward slope of the bell curve – the human equivalents of the Big-hearted Benevolents and Conscientious Capitalists.

Which means, we must pay them reasonable salaries, be able to share equity, and allow them to have some chance of an ‘exit’ so as to create wealth for founders and employees, something that is possible through the legal structure of a for-profit social enterprise.

Lastly, partnerships are key to execution and scale. Social businesses need partners who will help them use their labs for prototyping equipment, test their medical device in clinics or distribute their product. Here too, the bell curve of altruism will come into play.

While a few partners will enthusiastically support your cause, with little expectation of a return, true scale will only come from partners who will charge for services rendered.

I believe that we need to recognise that not everyone is an Amazing Altruist. If we have to expand the pool of funders, people and partners who can help us in our journey of addressing social problems at scale, we need to leverage structures that give them more than just social impact.

Of course, some checks and balances are required to ensure that we guard against mission drift, but with those protections in place, I do think we can leverage the benefits that are on offer.

Striding their way to create social impact – insights from women entrepreneurs

Women entrepreneurs, for decades, have had a significant role to play in the development of local economies, which further fed into the overall development paradigm. The contemporary startup-led ecosystem has also witnessed a surge in women entrepreneurs who have successfully carved a niche for themselves. Around 14 percent of the businesses in India are currently owned by women. Several of these businesses not only showcase tremendous growth potential but are also excellent examples of innovative social welfare solutions.

Despite such developments, much like everywhere else, the incremental growth of women-led businesses in India is often hindered by persisting gender biases and preconceived notions. Fighting all odds, the stories of their startup journeys, especially as women, are powerful and inspiring.

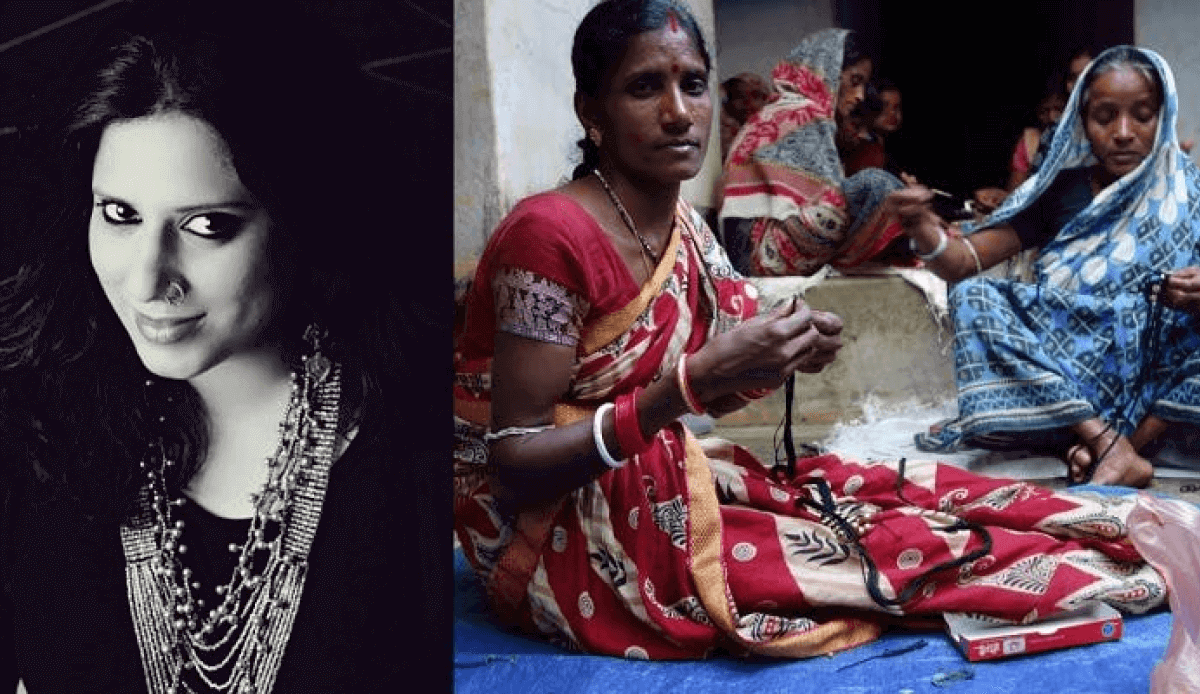

Gina – promoting artisans from rural hearts of India

Gina Joseph has always had an eye for appreciating art and the history it entails. This ‘accidental entrepreneur’ took a break from her corporate career and decided to pursue her passion in arts through Zola India.

Zola India was born in 2014 out of its founder’s pure love and admiration for Indian art, culture, and heritage. An online jewellery platform, it sources designs and products from the rural heart of India, providing a necessary link between the artisans and modern-day marketplaces.

Working closely with rural artisans, Gina realized that the absence of the right market connects often pushes the rural youth away from their traditional art. For instance, the Pattachitra (palm leaf etching) artisans of Odisha end up selling their hand-painted/etched scrolls to middlemen at extremely low prices, earning just about the money to survive on a day-to-day basis. In order the revive the art form, Zola India is currently working with about 10 Pattachitra artists and 20 women Dhokra (bronze casting technique) artisans in Odisha. Dealing with the artisans directly, the involvement of middlemen has been reduced to a large extent, helping artisans get better prices for their products.

Since its inception, the organization has been able to impact the lives of rural artisans in more ways than one. “It was such a moment of joy for me when one of my artisans from Odisha proudly told me that she could now afford better education for her two children, while another artisan from Andhra was able to pay part of her home loan through her earnings from Zola India,” says Gina.

More so, designs at Zola India are always a collaborative effort of technique and insights from the artisans. As a brand, it allows rural and folk artisans to express themselves through wearable art, thereby allowing them to realize sustained economic empowerment by conducting regular design intervention and innovation workshops across rural India. Zola India has been working with Dhokra and Pattachitra artists from Orissa, Toda embroidery artists from Tamil Nadu, Wall Mural art and Aranmula mirror artists from Kerala, Leather puppetry and Lac Turnery from Andhra Pradesh, and Bidri from Karnataka.

Anuradha – bridging the ‘English medium’ gap

Coming from a traditional Baniya background in Rajasthan, Anuradha broke all barriers and stereotypes when she decided to set up her own startup. “While pursuing higher studies was still encouraged, the idea of ‘working women’ was quite alien to my culture when I started off,” recalls Anuradha.

Visiting her hometown in 2015, she realised that there was a growing insecurity among women her age, mostly housewives, due to the lack of English education. This often led to low self-esteem even while coping with the most mundane day-to-day situations. “I could relate to the women at so many levels and their stories often reminded me of my struggle to find a footing,” says Anuradha.

Realising the need, Anuradha started posting interactive video modules on her Facebook page which generated a lot of traction from eager English learners. Seeing the response, she decided to take a plunge into entrepreneurship and launched an Android app to learn English through Hindi and Bengali in Dec 2016. This is how Multibhashi was born.

With an aim to build capacities of its users, Villgro- and Startup Oasis-supported Multibhashi focuses on early-stage English learners who want to learn communicative English. Since inception, the Multibhashi app has modelled English learning through 10 Indian languages and has been downloaded by close to a million users.

Going beyond its userbase, Multibhashi also employs a large number of women and provides them with an opportunity to earn a living. “All our women employees have been able to hone their skills in the process, and have become more confident,” beams the proud Founder of Multibhashi.

Ekta – going organic all the way

Aiming to build a sustainable, organic, and resilient community, Ekta Jaju started working with small farmers in Nadia districts of West Bengal and converted them to organic farming in 2012. “I started working on a business model that was financially sustainable and scalable in the organic space, where my main aim was to keep farmers’ interest in mind,” says Ekta.

ONganic Foods is an agri-organic social enterprise which works across the value chain – farming, processing, R&D, and domestic sales – and connects small organic farmers to markets by supporting them to convert back to organic farming and growing indigenous varieties.

Recalling the challenges in her startup journey, Ekta emphasizes that failure is just not an option, especially for social entrepreneurs. “If you face a certain challenge, or find a certain blockage in your path, you need to find an alternate route to reach your goal. We have to constantly remind ourselves of the many hopes and opportunities of our beneficiaries. It’s a big responsibility,” explains this committed entrepreneur.

Currently, ONganic works with 300+ farmers and aims to impact 10,000 farmers by 2025. In the last two years of operations, ONganic has supported farmers to increase their profitability through organic cultivation and value addition.

Ambika – ensuring farm fresh produce from Western Odisha

“My decision to move to Bhawanipatna in Kalahandi district of Odisha and ditch a corporate career to start my own venture was questioned by many,” recalls the Co-founder of ZooFresh.

ZooFresh Foods is an agri-tech startup, creating post-harvest management technologies and retailing platforms for meat products (chicken, fish, and eggs) in Eastern India, especially in economically backward zones like Western Odisha.

Working in such backward regions was a major lifestyle change for Ambika. Despite being constantly overworked and underpaid, it took a while to see any tangible impact of all her hard work. Coupled with this was the frustration of coping with a plethora of challenges associated with stereotyping women entrepreneurs.

To deal with this, Ambika quickly learnt the skill of leveraging all the advantages one gets in lieu of being a woman entrepreneur like government-sponsored programmes and schemes as well as the benefits of the general inclination towards women-run businesses in the private sector ecosystem. “I have lately come to realise all my advantages as a woman entrepreneur. We, as a group, are a micro-minority, and when we speak, everyone listens! You will be able to network better (since there are so few of us, we get remembered easily), and you will get ample invites for critical events which you should leverage,” explains Ambika.

Besides promoting fresh farm produce, Ambika envisions ZooFresh as having a significant impact on women as well. ZooFresh now works with a large number of tribal women, who are the company’s micro-entrepreneurs and distributors in remote tribal communities.

For women entrepreneurship to truly thrive in India, we need to look for more investment support for gender-diverse founding teams through discovery programmes like iPitch.

Lonely at the top?

It sure could be … but don’t worry

P. Ravi Shankar

Advisor – Menterra Venture Advisors

Some years ago, when I had just begun my Executive coaching journey, I met the CEO of a firm at his corner office on the 9th floor. It was 9 p.m on a Friday evening. He had just seen off his Board members after a—as he told me later—tough meeting. There was no one else on the floor, and as I entered I remember saying to him, “It sure is lonely here” to which he replied mischievously, “and windy too.”

I was lucky to be with this CEO who still had his wits and sense of humour intact after a gruelling board meeting. Others aren’t so lucky.

My interactions with founders and promoter CEOs of other companies, large, small and start-ups were not half as entertaining most of the time. Many of them (privately expressed) were despondent and extremely stressed although most tried not to show it. Many of them told me that they felt lonely most of the time and had no one to confide in, especially when it came to taking difficult decisions. This is in spite of the fact that in large and more “established” companies there is a deep hierarchy of talent and specialists, both internal and external, that the CEO could rely on. Turns out, the buck ultimately stopped at the corner office and it’s occupant had to, ultimately, carry the cross.

A recurrent theme was their inability to take control of functions that were not their core, which were in most cases, sales and marketing. This, coupled with their inability to hire resources, especially at the start-up stage, to manage these functions make them put in extremely long hours, with more misses than hits and a lot of ensuing frustration. Another recurring frustration was the inability to be on top of everything as the company grew and newer people were hired. A third, was the feeling of bitter betrayal when someone critical (and seemingly loyal) left to join the competition.

These were just a few recurring problems, among many others, that led to frustration and feelings of acute loneliness. Some founders, took the decision to wrap up and go back to jobs and organisations, but most went on to achieve success to various degrees.

How do we understand these symptoms? How do we find answers to these questions, pleas, frustrations, and stresses, some of which lead to deep psychological scars, strained relationships with families and co-founders, other organisational issues, and other manifestations including physical and mental illnesses?

In my experience, both as a management practitioner and coach, I have realised that every situation is different and most problems faced in the corner suite are contextual.

However, there are several common root causes that helps one suggest some general solutions to the issue of loneliness at the top.

My experience also is that happy entrepreneurs create happy, more engaged workplaces, and these make for successful business success with the judicious management of resources, great products and other commendable management strategies.

Think about it. When did we last look at some aspects of individual happiness as non-negotiable? When did we last sacrifice something at work that could be safely delegated for something that gave us more happiness?

I think everyone would agree that happiness at work and loneliness at work are related. Happy persons generally are not lonely. More on work place happiness later – perhaps in another paper. Let’s now get back to the issue of loneliness at the top.

The root cause of work place loneliness is not only related to happiness at work. Let’s look at some of the other causes.

- Fear of not knowing what is happening around him/her. This is a constant fear among most entrepreneurs I have met and dealt with, especially first time entrepreneurs. I would help to develop dash boards from the beginning. Developing structured reporting frameworks will save time otherwise spent on unnecessary meetings. Understand that you will never be in total control, nor are you expected to ever be. Develop a list of key things you should know. The rest is a bonus. Let go, get a life, and stop worrying. The core issue here is trust which is the biggest ingredient of happiness and comfortable environments.

- Feeling betrayed when someone leaves your organisation. This will happen, again and again. If you create a happy organisation, it is more likely that people will want to stay. However, even then, people leave for all sorts of reasons, some beyond your control. In the event that they do leave, make sure they leave with praise for you and your company. One person leaving you does not mean you begin to distrust the next person hired. It’s up to you to share your happiness through trust.

- Just as you share happiness to reduce loneliness, from the beginning plan to share your wealth with those who contribute to your well-being and happiness. Once you have decided to , it doesn’t pinch when you actually give it away.

- Keep the entrepreneurial magic alive. There are limits to your ability to know everything , be in every meeting or meet every customer or competitor. Prepare to break your monolith companies into small manageable parts, parts that your best performing managers can manage and grow. Yes, doing this involves sacrificing some control, but that sacrifice may well be the key to your success and happiness. Create growth plans for people so that they are in tandem with your company’s growth. And most importantly, communicate your plans. In the process, you may make great friends in your journey to great success, then where’s the loneliness? Everyone fails. But they rise again with the help of their teams.

- Remember, help comes from unexpected quarters. Many years ago during the “industrial relations” phase of my career, I was terribly lonely much of the time. It was a time when careers of a large numbers of people (and by extension, the lives of their families), especially blue collar workers or line supervisors, rested on me. My managements vested on me the responsibility to close down units or bring up labour productivity sharply and stave off closures. In all these times, I had help and support from traditional ‘foes’ ( Union leaders) who worked shoulder-to-shoulder with me and staved off imminent closures. Similarly, entrepreneurs need to look beyond traditional sources of advice. A failed entrepreneur, a distributor or even a competitor could become your best advisor. Case studies off the internet could be a great teachers. Sometimes, dig deep into your company hierarchy and you will find great solutions. Some of the most creative solutions have come from ‘floor level’ employees and in recent times from bright young people unfettered by hierarchy or tradition.

- Make sure you have a competent Board, selected for their independent thinking and forthright views. Entrepreneurs seeking board control and Board members who will not disagree with them, are doing a great injustice to themselves and their companies. Discussions around strategy, even if many in the Board disagree with you, are refreshing and make you think. Maintain an open relationship with investors and key employees. Speak to them frequently, even informally. Everyone needs someone. Including you.

- Confide in people, even if you are not the “type”. Getting rid of your fears and anxieties even without any expectation of a solution, will make things better for you. Confide in your spouse, your children and co-workers. They will rally around you and sometimes come up with unexpected solutions.

- Don’t stop yourself from training in areas that are not the “CEO type” training. Some of the best CEOs I know are those who showed an inquisitiveness that was almost childlike. Many years ago, when I sought approval from my CEO to attend PMP classes as I had to oversee Project Managers, my CEO joined in as a fellow student. People development, for example, is not a fuzzy area as it is most often perceived—it is a hard, focused area, training in which will benefit CEOs greatly. Business Development / Sales and Marketing skills is another area in which start-up CEOs (largely technologists) should receive formal training. Training is not an admission of a failure. It is actually an acceptance of your shortcomings and yearning to learn more.

- Have group activities in your companies and become part of it. Task forces, off-sites, celebrations. Make yourself central to some of them. You will see the difference.

- Stay fit. Take time off every day for some exercise, a brisk walk, a jog, a swim, to play a sport, whatever. It is a great way to not only ensure your own well-being but also to meet very interesting people who will treat you as an individual, and not a boss or a work colleague. It’s important and refreshing to be amidst such people.

- Above all, remember that failure is a great experience and it directly increases the probability of success. There are great lessons to be learnt from every failure.

Menterra has attempted to address this issue of loneliness and happiness directly. As a fund we remain focused on and committed to going beyond traditional parameters of success. We are a fund that goes beyond risk capital, one that creates impact with a scale that we have demonstrated again and again through our deep commitment to the entrepreneurs in whose dreams we have invested.

We also have agreed to have a buddy system within the Menterra founder group so that we reach out to each other in times of need. We will continue to explore this question of loneliness and happiness, candidly, forthrightly, and sensitively, with our entrepreneurs, so that they, their senior teams and their businesses are happy, enabling them to run happy and impactful companies that build happy communities and societies

India@70: The Anxiety of Asymmetry

The dream of inclusive, sustainable development will remain unfulfilled unless we acknowledge and address the deep imbalances that threaten to weaken the idea of this nation.

On August 15, 2017, Independent India will be 70. Is India@70 significantly different from India at 50? If yes, how, and what is the implication of this for our collective desired future: inclusive, sustainable development for India, that can contribute to environmental resilience and global peace?

Indeed, the India of 2017 is significantly different from the India of 1997. For me, India@70 is characterized by three asymmetries:

- The Aspiration vs Attainment Asymmetry at the level of self-concept of individuals

- The Rights vs Responsibility Asymmetry at the level of how individuals relate to each other

- The Technology vs Mythology Asymmetry at the level of how individuals relate to the environment and other aspects of existence beyond human control

The collective scope of these three asymmetries spans everything that human beings are and experience.

Yet, the aspirational explosion is matched with an attainment implosion. As an example, see PRATHAM’s Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) for 2016. It showed that while enrollment rates in our schools were above a very creditable 95 percent, roughly one out of four children in Standard VIII could not read Std II texts and 57 percent of Std VIII students could not correctly solve a three-digit by one-digit division problem.

With such a disadvantage in educational attainment, how can we ever encase the much-heralded ‘demographic dividend’? It seems more like a demographic disappointment. Higher education—or even acquisition of vocational skills—is difficult, if not impossible, for these young people and that has implications for their employability. Yet, they must live and make a living. So, the school drop-outs of yesterday, whose aspirations have been kindled but means of attainment extinguished, vent their ire against ‘the system’ in multiple ways, such as joining gangs of vigilantes. Given that the numbers of such young people run into millions, this will be a huge socio-economic problem, to which we have not yet woken up as a nation.

Unless something is done in the next five years, it may be too late. We need a national mission for promoting self-employment, starting with skill, business and entrepreneurial training, followed by start-up financing and handholding until the self-employed persons stabilize their enterprises. It will be impossible for India to have inclusive, sustainable development without this.

This aspiration-attainment asymmetry is not only among the youth or the lower-income groups: it exists in the older and richer segments as well. As a society, we need to figure out how to curb the need for obsessive consumption and constant upgrading of our living standards, given the high cost to the environment and to ourselves. We, the older and more privileged ones, need to practice the ancient wisdom of “simple living, high thinking,” preachy as it may sound.

Unless the balance is restored in each dyad, we will remain deeply flawed as a nation.

Unless the balance is restored in each dyad, we will remain deeply flawed as a nation and are unlikely to achieve the cherished, consensual goal of inclusive, sustainable development, contributing to environmental resilience and global peace. This is the meta-task cut out for development thinkers and social change activists, even as we go about whatever it is that is our self-defined day-job, or writing articles that few may read.